Notes On Computer Systems - A Programmer's Perspective

by Randal Bryant

- Things I should revise once finished:

- Chapter 1 - A Tour of Computer Systems

- Chapter 2 - Representing and manipulating information

- Chapter 3 Machine-Level Representation of Programs

- 3.1 A Historical Perspective

- 3.2 Program Encodings

- 3.3 Data Formats

- 3.4 Accessing Information

- 3.5 Arithmetic and Logical Operations

- 3.6 Control

- 3.7 Procedures

- 3.8 Array Allocation and Access

- 3.9 Heterogeneous Data Structures

- 3.10 Combining Control and Data in Machine-Level Programs

- 3.11 Floating-Point Code

- 3.12 Summary

- Chapter 4 - Processor Architecture

- 4.1.3 - Instruction Encoding

- 4.1.4 Exceptions

- 4.2 Logic Design and the Hardware Control Language HCL

- 4.2.1 Logic Gates

- 4.2.2 Combinational Circuits

- 4.2.3 Word-level Combinational Circuits

- 4.2.4 Set Membership

- 4.2.5 Memory and Clocking

- 4.3 Implementation of a CPU from an ISA (renamed from the real chapter name for my own understanding)

- 4.3.1 Organizing Processing into Stages

- 4.3.2 Hardware Structure

- 4.3.3 SEQ Timing

- 4.4 General Principles of Pipelining

- 4.4.1 Computational Pipelines

- 4.5 Building a Pipelined CPU

- Chapter 5 Optimizing Program Performance

- 5.1 Capabilities and Limitations of Optimizing Compilers

- 5.2 Expressing Program Performance

- 5.4 Eliminating Loop Inefficiencies

- 5.5 Reducing Procedure Calls

- 5.6 Eliminating Unneeded Memory References

- 5.7 Understanding Modern Processors

- 5.8 Loop Unrolling

- 5.9 Enhancing Parallelism

- 5.11 Other limiting factors

- 5.12 Understanding Memory Performance

- 5.13 Real-world performance improvement techniques

- 5.15

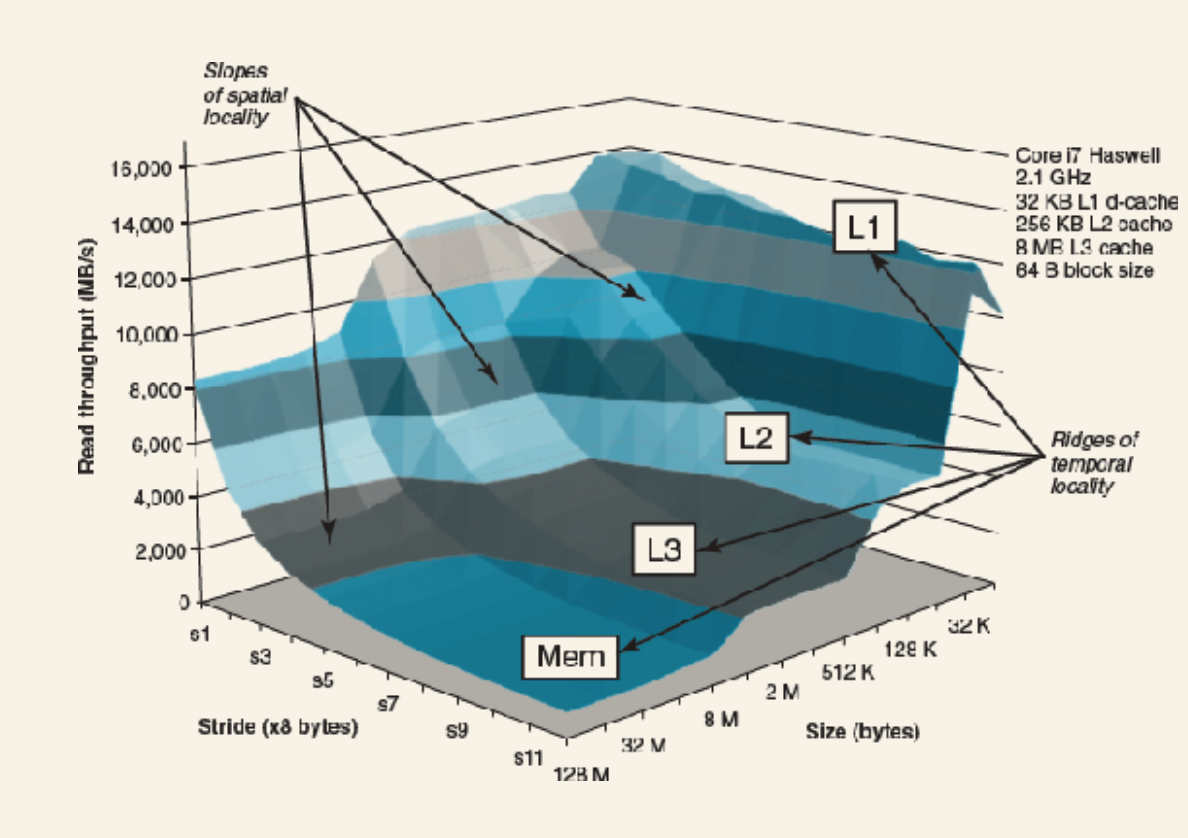

- Chapter 6 The Memory Hierarchy

- Chapter 7 Linking

- 7.1 Compiler Drivers

- 7.2 Static Linking

- 7.3 Object files

- 7.4 Relocatable Object Files

- 7.5 Symbols and Symbol Tables

- 7.6 Symbol Resolution

- 7.7 Relocation

- 7.8 Executable Object Files

- 7.9 Loading Executable Object Files

- 7.10 Dynamic Linking with Shared Libraries

- 7.11 Loading and Linking Shared Libraries from Applications

- 7.12 Position-Independent Code (PIC)

- 7.13 Library Interpositioning

- 8.1 Exceptions

- 8.2 Processes

- 8.4 Process Control

- 8.5 Signals

- 8.6 Nonlocal Jumps

- 8.7 Tools for manipulating processes

- 8.8 Summary

- 9.1 Physical and Virtual Addressing

- 9.2 Address Spaces

- 9.3 VM as a Tool for Caching

- 9.4 VM as a Tool for Memory Management

- 9.5 VM as a Tool for Memory Protection.

- 9.6 Address Translation

- 9.7 Case Study of a real system (i7)

- 9.8 Memory Mapping

- 9.9 Dynamic Memory Allocation

- 9.10 Garbage collection

- 9.11 Common Memory-related Bugs in C

- 9.12 Summary

- 10.1 Unix I/O

- 10.2 Files

- 10.3 Opening and closing files

- 10.4 Reading and writing files

- 10.5 Unbuffered / Buffered I/O

- 10.6 Reading File Metadata

- 10.7 Reading Directory Contents

- 10.8 Sharing Files

- 10.9 I/O Redirection

- 10.10 Standard I/O

- 10.12 Summary

- 11.1 The Client-Server Programming Model

- 10.2 Networks

- 11.3 The Global IP Internet

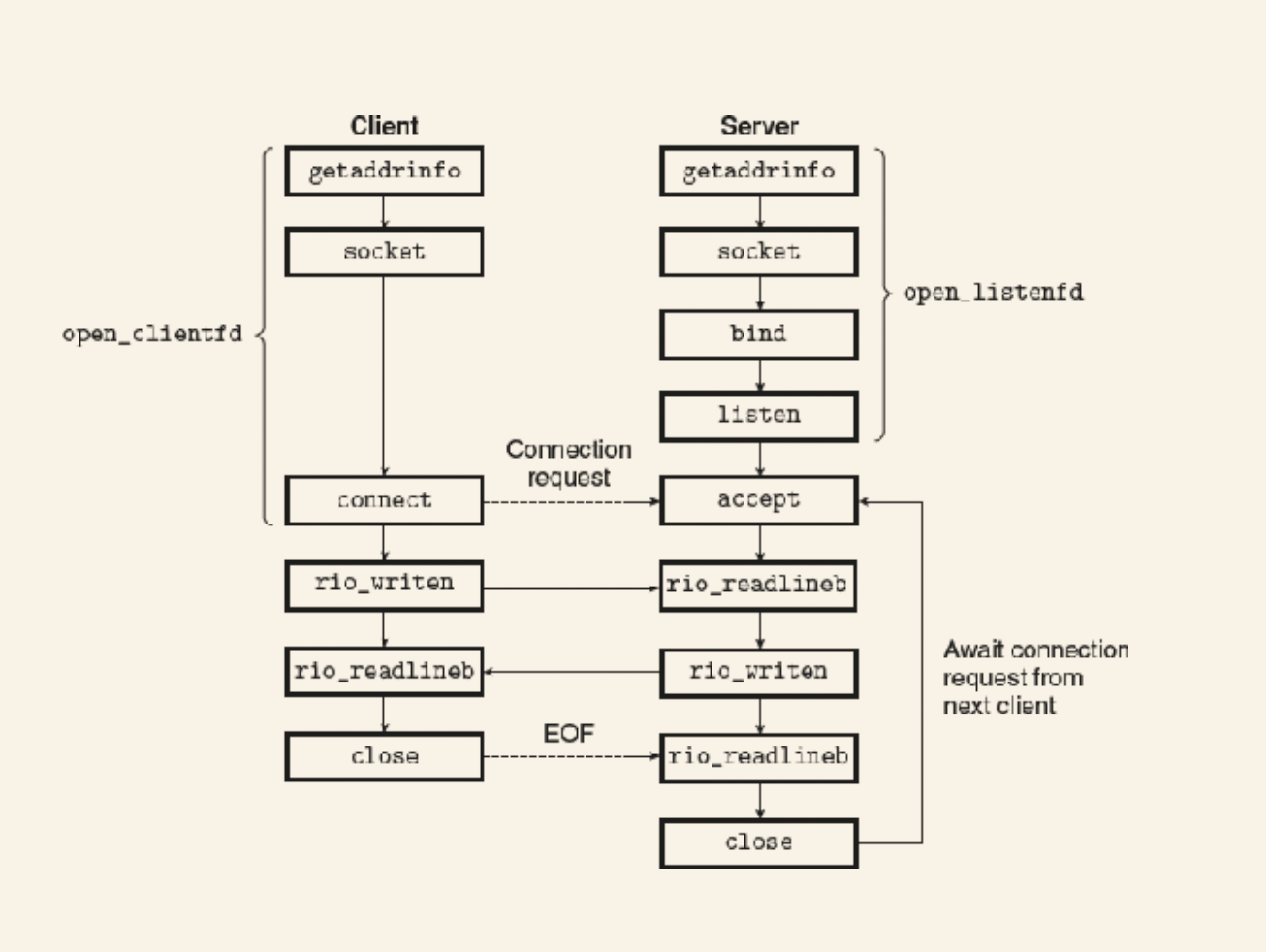

- 11.4 Sockets Interface

- 11.5 Web servers

- 11.6

- 12.1 Concurrent Programming with Processes

- 12.2 Concurrent Programming with I/O Multiplexing

- 12.3 Concurrent programming with threads

- 12.4 Shared variables in threaded programs

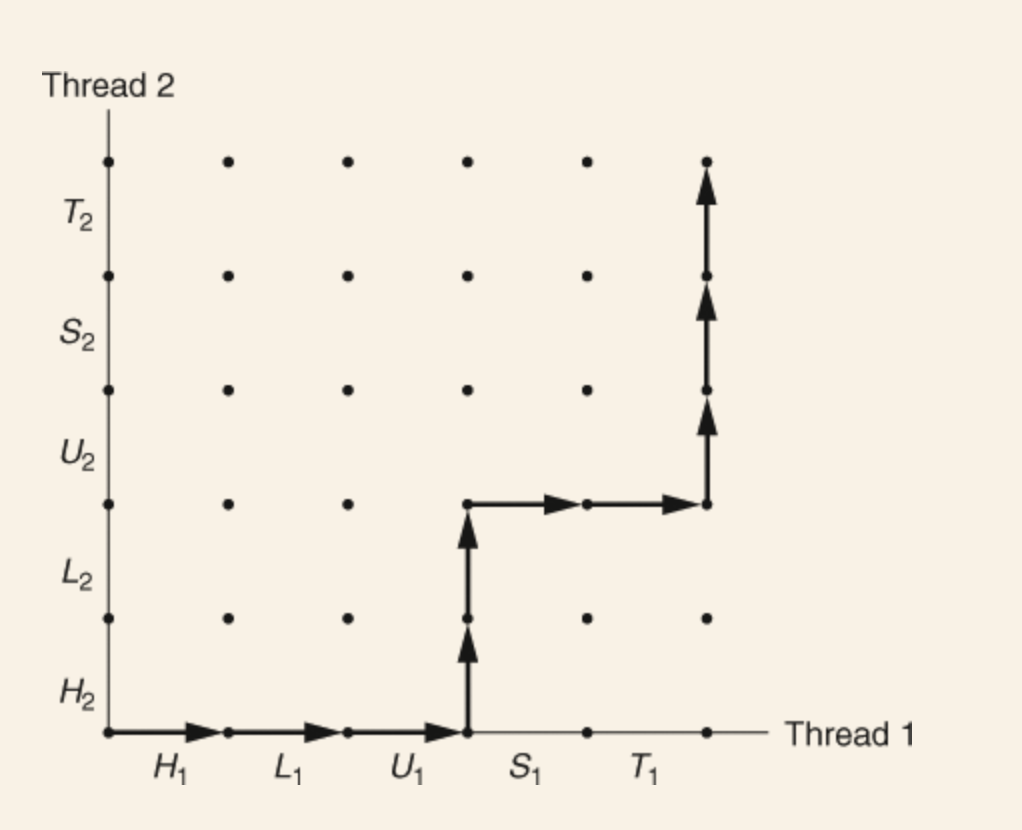

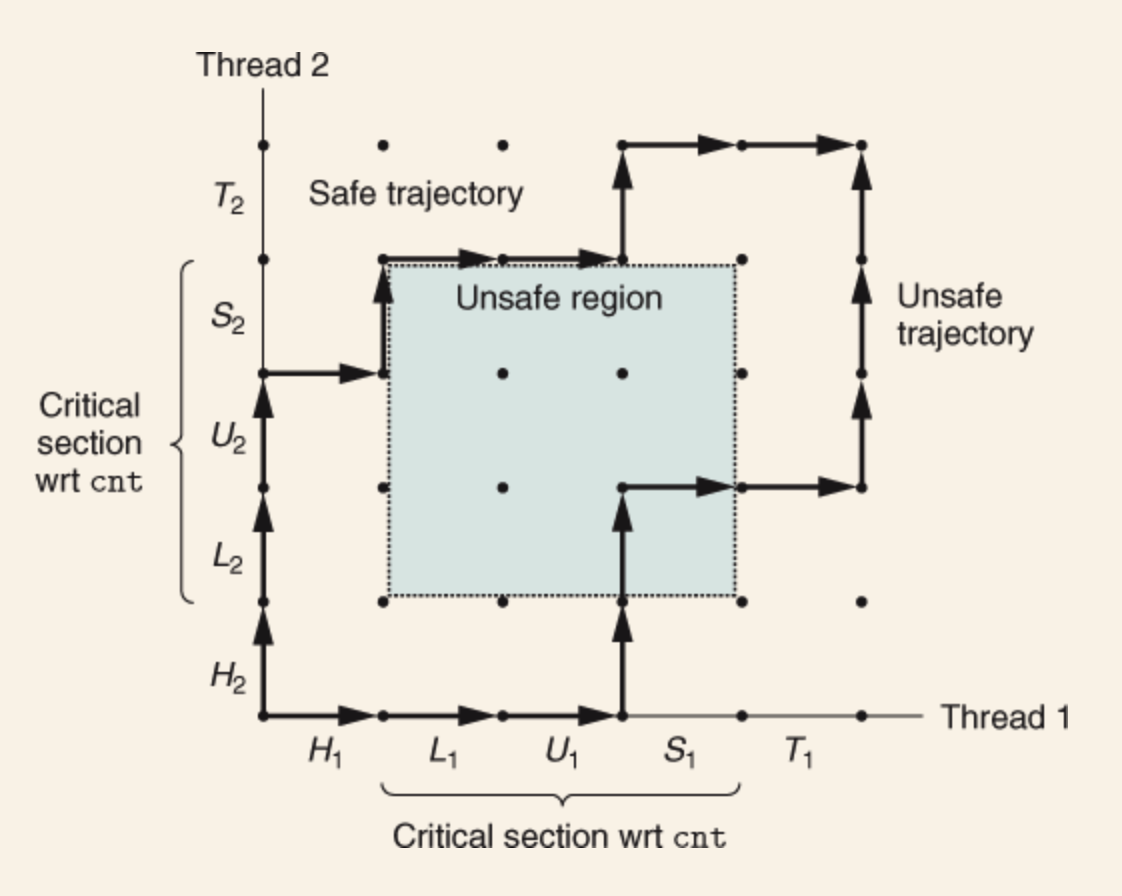

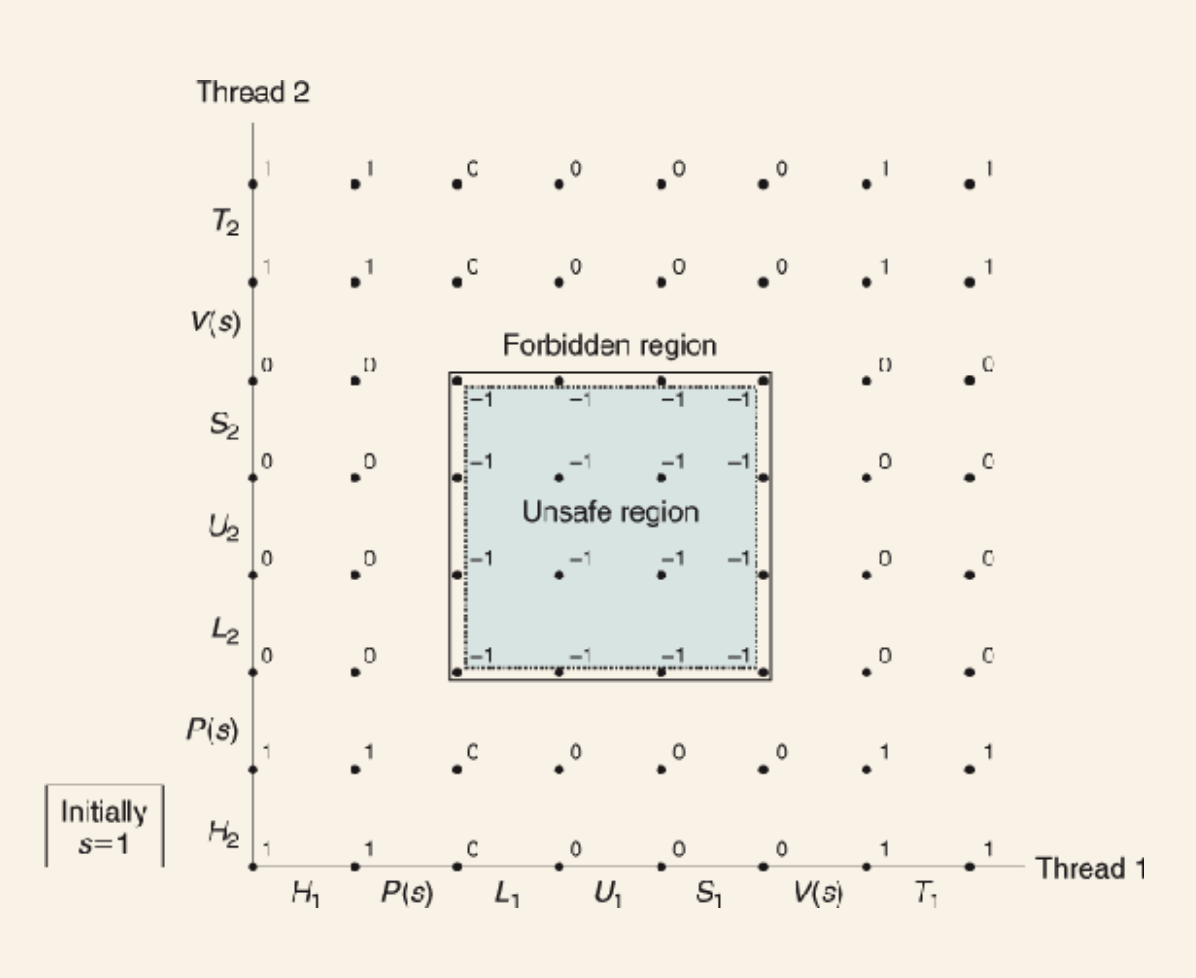

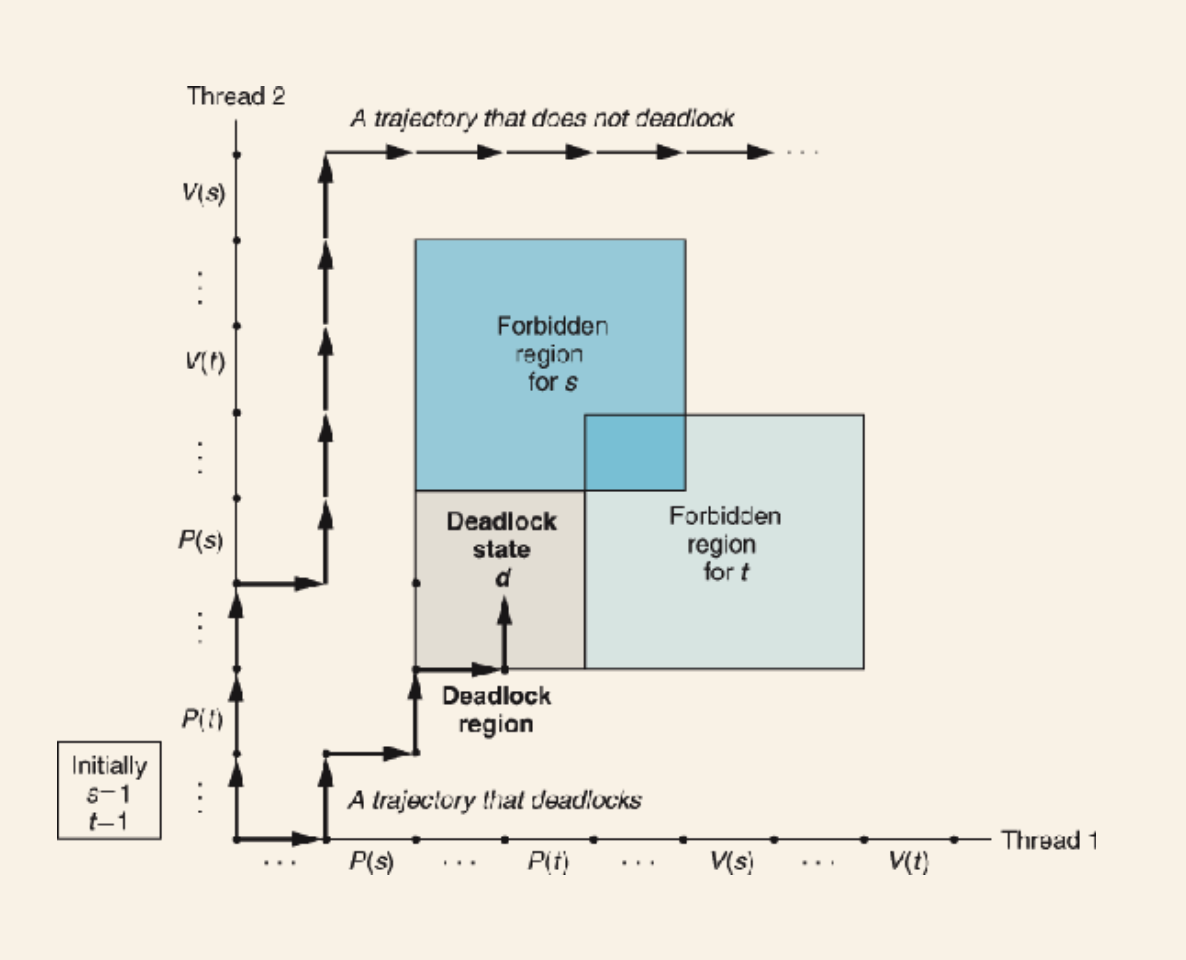

- 12.5 Synchronizing threads with semaphores

- 12.6 Using threads for parallelism

- 12.7 Other concurrency issues

- 12.8 Summary

Things I should revise once finished:

- Two's compliment and its effect on the possible arithmetic

- Logical/arithmetic bit shifting, especially in relationship to the integer encoding used.

Chapter 1 - A Tour of Computer Systems

All information in a system is just bits. The only thing that distinguishes them is the context in which we view them. A text file is still just bits, but a "text file" is a file of bits that only correspond to text.

Compilation

Compilers transform source into executable object programs|files. Four stages:

- Preprocessing - Macros, includes, etc are bundled into a single text file,

.i - Compilation - Translates the

.iinto assembly text file.s. Useful as a common language between different languages & processors. - Assembly - Translates the assembled file into machine language binary file known as a relocatable object program,

.o. - Linking - Merges other object files referred to by included headers into a single executable.

Elements of a machine

Shells: A command-line interpreter

Hardware

Buses

- Electrical conduits that carry bytes between components.

- Typically designed to transfer fixed-sized chunks of bytes known as

words. - The number of bytes in a word (word size) is a fundamental system parameter that varies across systems. - Most systems have a word size of 4 bytes (32 bit) or 8 bytes (64 bit).

I/O

- Each I/O device is connected to the I/O bus by either a controller or adapter. - Controllers are built-in (to either the motherboard or the device), adapters are separate cards that plug into the motherboard.

Main memory

- Temporary storage for data used by the program.

- Physically a collection of dynamic random access memory (DRAM).

- Logically, memory is organized as a linear array of bytes, each with its own unique address (array index) starting at zero.

- The size of various C data types (short, etc) vary depending on machine type (x86-64, etc).

Processor

Executes instructions stored in main memory. At its core is a word-size storage device (a register) called the program counter. At any point the PC points at (container the address of) some machine-language instruction in main memory. For the duration of the time the CPU has power it will execute the instruction pointed to by the program counter and updates the PC to point to the next instruction.

Appears to operate according to a simple model defined by its instruction set architecture. In this model, instructions are executed in a strict sequence.

There are only a few of these simple operations and they revolve around main memory, the register file, and the arithmetic/logic unit (ALU).

Register file: small storage device that consists of a collection of word-size registers, each with a unique name.

ALU: computes new data and address values.

Example instruction in the instruction set:

- Load: Copy a byte or word from main memory into a register, overwriting previous data.

- Store: Copy a byte or word from a register to a location in main memory, overwriting.

- Operate: Copy to registers to ALU, perform arithmetic operation, and store result in register, overwriting.

- Jump: Copy word from the instruction itself and copy it into the program counter.

CPUs appear simple, but actually they have a lot of complex mechanisms to speed up program execution. The microarchitecture is actually how its implemented.

DMA: Direct memory access - Data travels direct from disk into ram, bypassing the CPU.

Performance:

A lot of the slow down in processing is the overhead of moving data from disk to memory to registers to display devices. So a lot of effort is put into increasing the efficiency of the I/O. Due to physical laws, the smaller the device the faster they are.

Storage performance:

- So disk is large but slow.

- Ram is smaller, but faster (10,000,000x disk).

- Register file is much smaller (few hundred bytes), but much faster (100x RAM access)

There's a processor-memory gap: it's easier and cheaper to make processors faster than it is to make main memory faster. To account for slow memory we have cache memories (caches).

Caches:

- Temporary staging area for information the CPU is likely to need in the near future.

- L1 cache holds 10s of K of bytes and can be accessed almost as faster as the register file.

- Large L2 holds 100s of K of bytes. 5x longer to access than L1. But still 5-10x faster than ram.

- L1/L2 implemented using SRAM (static random access memory).

- Newer systems have three levels of cache.

- Caching relies on exploiting locality: the fact that programs tend to access data in localized regions.

Storage hierarchy:

- All storage in a system forms a hierarchy: starting with registers -> L1 ... RAM -> Disk -> Remote Disk.

- As we move down, storage gets slower, large, and cheaper.

- L0 is registers.

- Main idea: each level acts as cache for the layer below.

Operating system:

Layer of software interposed between apps and hardware. All attempts to manipulate hardware must go through OS.

It has 2 purposes:

- Protect hardware from misuse by apps

- Provide apps with a simple and uniform mechanism, for manipulating often wildly different low-level hardware devices.

The OS does this by some fundamental abstractions:

Processes: abstractions for the processor, main memory, and I/O.

- When a program is run the OS provides the illusion that its the only one running on the system.

- Appears to have exclusive use of CPU, main memory, and I/O.

- Multiple processes can be running concurrently with each appearing to have exclusive use.

- The OS does this with a single core by interleaving the instructions of separate programs. - Known as context switching. - Each process is composed of the values of the PC, the register file, and the contents of main memory. Each time it context switches, these are saved and restored. - System calls are used to request context switching.

- The transition from one process to another is managed by the OS kernel. - When the program requires action from the OS it uses a system call like read or write from a file, which transfers control to the kernel. - The kernel is not a separate process, its a collection of code and data structures the system uses to manage all the processes.

- Threads - Multiple execution units running in the context of the process - sharing code and global data. - Easier to share data between threads than processes. - Typically more efficient than processes.

Virtual memory: abstraction for main memory and disk I/O devices

- Provides a process the illusion it has exclusive use of memory.

- Each process has the same uniform view of memory: its virtual address space.

- Virtual address space from bottom to top (0 address to N) - Program code: code begins at the same fixed address for all processes. Fixed in size once it starts running. - Heap: run-time heap expands and contracts dynamically at run time based on calls to malloc and free. - Shared libraries - Stack: used for function calls, expands and contracts. - Kernel virtual memory: reserved for kernel, not accessible to user apps.

- Requires a hardware translation of every address.

Files: abstractions for I/O devices

- A sequence of bytes, nothing more, nothing less.

- All input and output in the system is performed by reading and writing files, using a subset of system calls known as Unix I/O.

- Simple but powerful way to have uniform view of all the varied I/O devices.

- Networks - From the POV of a process, the network can be viewed as another I/O device.

Amdhal's law

A speed up of a part of system is dependent on how significant that part is to the overall system; its fraction of the overall time it takes to run the operation. So a 6x speed up for a part of the system that is 50% responsible is only 3x in the end.

Concurrency & parallelism

Concurrency: general concept of a system with multiple, simultaneous activities. Parallelism: the use of concurrency to make a system faster.

Types of concurrency

- Thread-level: - We get thread-level currency in a single process, even though its simulated. - Multi-core systems - Multiple processors in the system, each with their own L1, registers, etc. - Hyperthreading - Essentially gives hardware support to the idea of threading. - Some parts have multiple copies like program counters and register files, while sharing an ALU. - Allows the CPU to take better advantage of resources. For example, while it waits to load data into cache, the CPU can execute a different thread. - For single process to take advantage of multiple processors or hyperthreading, the program must have been written with it in mind.

- Instruction-level parallelism - Allows the processor to execute multiple instructions per clock cycle. - Done via pipelining, where discrete stages of an instruction are broken into steps that can be ran in parallel.

- Single-instruction, multiple-data (SIMD) parallelism - Special hardware that allows a single instruction to cause multiple operations to run in parallel. - Mostly used to speed up processing image, sound, and video.

Regardless of the parallelism used in running something, the simple sequential model of execution implied by the CPUs instruction set is always maintained.

Virtual machines: Abstracts the entire computer, including the OS, the processor, and the programs.

Chapter 2 - Representing and manipulating information

Base 10 makes sense for humans (10 fingers and all that), but base 2 makes more sense for storage of information due to the simplicity of representing two states.

Three representations of numbers:

- Unsigned: numbers greater than 0

- Twos-complement: positive or negative

- Floating point: Is not associative due to the finite precision of representation

Pointers contain the address and a type of a byte in memory. Binary notation for a byte is verbose, so instead we use base-16, or hexadecimal.

Hexidecimal uses the chars 0-9 and A-F, giving 16 possible values. A single byte can range from to . C uses 0X to indicate hex values.

-

Problems:

-

Problem: 2.1

- 0x39A7F8: 0011 1001 1010 0111 1111 1000

- 1100 1001 0111 1011: 0xC97B

- 0xD5E4C: 1101 0101 1110 0100 1100

- (00)10 0110 1110 0111 1011 0101: 0x26E7B5

-

Problem 2.2:

-

When X is a power of 2^n, the binary will be 1 followed by n zeroes

-

To convert to hex, let

n = i + 4j, where 0<=i<=3. Where the leading hex isi2^i, followed by j hex 0s. -

So 2048 = 2^11

-

So n = 3 + 4*2

- i = 3

- j = 2

-

So hex: 0x800

-

n 2^n 2^n hex 19 524288 0x80000 14 16384 0x4000 16 65356 0x10000 17 131072 0x20000 5 32 0x20 7 128 0x80

-

-

-

Problem 2.3

- To convert decimal x to hex, we repeatedly divide x by 16, giving x = q * 16 + r for each iteration

- We then use the hex for r as the least significant digit and the generate the remaining digits repeating the process on

q.

- We then use the hex for r as the least significant digit and the generate the remaining digits repeating the process on

- To convert from hex to decimal, take each hex digit and multiple it by 16^n, where n is the position of the digit, with the right-most digit starting at 0. Add each term together.

-

Decimal Binary Hexadecimal 167 1010 0111 0xA7 62 0011 1110 0x3E 188 1011 1100 0xBC 52 0011 0111 0x37 136 1000 1000 0x88 243 1111 0011 0xF3

- To convert decimal x to hex, we repeatedly divide x by 16, giving x = q * 16 + r for each iteration

-

Problem 2.4

- 0x503c + 0x8 =

- Not doing these as I don't get how to add in a different base

-

Word size: the nominal size of pointer data. The size of an address puts a limit on the maximal addressable space, so 32 bit words, gives a limit of 2^32 - 1 = 4,294,967,295 bytes (4GB), as that's the total number of bytes that can be individually addressed using 32 bit words. 64-bit has 16 exabytes of addressable memory.

C data types

- Signed or unsigned ints

charis a singe byte, usually, but not necessarily, for storing a character- Some types vary based on the word size of the systems the programs are built for. But there are standardized types like

int32_t - Whether its signed or unsigned is up to the programmer

Objects that span multiple bytes:

- We need two conventions: - what the address of the object shall be - how we order the bytes in memory

- Virtually all machines, multi-byte object is stored as a contiguous sequence of bytes with the address of the object the smallest address of the bytes used - E.g if a 4-byte in has address 0x100, then the bytes 0x100, 0x101, 0x102, 0x103 are used.

- Once we know the bytes, we now need to know how the bytes are ordered to represent the object - Little endian: least significant byte comes first - Big endian: most significant byte comes first - Most intel use little-endian - Arm is bi-endian - can do either, up to the OS. iOS and Android are both little-endian - Which is chosen has no intrinsic advantage, but machines operating over a network have to agree.

Problems:

- 2.5 - A: 21, 87 - B: 21 43, 87 65 - C: 21 43 65, 87 65 43

- 2.6 - A:

0000000000110101100100010010000101001010010101100100010010000100- B: 21 bits - C: everything else

Strings are encoded as an array of characters terminated by the null (value: 0) character. Each character is represented by some standard encoding, with ASCII being the most common.

The ASCII code results in any digit x by represented by 0x3x and the null character is 0x00. That is the same across all platforms, meaning text data is more platform independent that binary data.

Problems:

- 2.7 - 0x61 0x62 0x63 0x64 0x65 0x66 -

strlendoesn't give give the length including the null character

If we convert some source code to machine code, the resulting bytes will be very different depending on OS and instruction set/machine. Meaning binary data is rarely portable.

A key concept is that from the perspective of the machine, a program is simply a sequence of bytes.

2.1.6 Boolean Algebra

As we can easily represent binary code physically, it allows us to formulate an algebra that captures the basic principles of logical reasoning.

We can use the four boolean operations to operate on bit vectors, strings of 0s and 1s of some fixed length . For example, let and , then a & b, , and :

| & | | | ^ | ~ |

|---|---|---|---|

0110 | 0110 | 0110 | |

1100 | 1100 | 1100 | 1100 |

0100 | 1110 | 1010 | 0011 |

-

Problem 2.9:

- This uses 3 bit vectors to encode RGB values. Using bitwise boolean operators we can manipulate the colors.

- A

- 111

- 110

- 101

- 100

- 011

- 010

- 001

- 000

- B:

- Blue | Green = Cyan

- Yellow & Cyan = Green

- Red ^ Magenta = Blue

-

Problem 2.10

-

We can use bitwise operations to swap the values at an address as an element is its own additive inverse:

a ^ a = 0.Step 1: a - a ^ b Step 2: Can't be bothered to finish this

-

-

Problem 2.11

- A: k

- B: Exclusive or with itself is 0

- C: Skip when first == last

-

Problem 2.12

- A:

x & 0xFF - B:

x ^ ~0xFF - C:

x | 0xFF

- A:

-

Logical operators

- Different to their bitwise counterparts

- The time they equal is when the arguments are 0 or 1.

- Logical operators short circuit

-

Problem 2.14

x = 0x66; y = 0x39x & y:01100110 & 00111001 = 00100000 = 0x20x && y:0x01x | y:01100110 | 00111001 = 01111111 = 0x7Fx || y:0x01~x | ~y:01100110-

`00111001 = 11011111 = 0xDF` ~x || ~y:0x00x & !y:01100110-

`00000000 = 0x00` x && ~y:0x1

2.1.9 Bit shifting

<<shiftskbits to the left, droppingksignificant bits, padding with zeroes at the right end.- Associates left to right, so

x << j << k==(x << j) << k. - Right shifts - a bit more complicated - two types:

- Logical: Shifts fills the left end k zeroes

- Arithmetic: Fills left end with

krepetitions of the most significant bit. It might seem weird, but it's useful for operating on signed integer data.

- Practically all compiler/machine combinations use arithmetic right shifts for signed data. For unsigned, right shifts must be logical.

- Java:

>>arithmetic;>>>logical.

- Java:

- Shift sizes larger than the word size are weird and not specified by the C standard. Java uses modulo to get the remainder and use that. Basically, just use < wordsize.

2.2 Integer Representations

2.2.2 Unsigned encoding

Each bit has value 0 or 1. The latter indicates that should be included as a part of the numeric value, i.e. it contributes to it. So if the number is [1001], the number is 2^3 + 2^0 = 9. So for vector x, the binary to unsigned is defined as the sum of for .

Max range for is defined as the sum of for i through the range to . Which simplifies to .

Unsigned binary representation has the important property that every number between 0 - has a unique encoding as a w-bit value. Which is said to be a mathematical bijection meaning that it's two way: reversible.

2.2.3 Two's-Complement Encoding

Allows us to support negative numbers.

The most significant bit is called the sign bit. Its "weight" is , the negation of its weight in unsigned representation. When the bit is set to 1, the represented value is negative, when set to 0 the value is non-negative

- The rest of the numbers are the same as the unsigned. It's the sign bit that either zeroes out (in the case of positive integer) or is equal to -2 x sum-of-of-the-rest. Due to it being raised to +1 exponent and made negative.

The least representable integer is [1 0 0 .. 0 0] = , the most is [0 1 1 ... 1 1] = .

- Two's complement is also a

bijection. - Two's complement is asymmetrical: there's no positive counterpart to TMin. This happens because half the bit patterns represent negative numbers and half represent positive numbers. Since 0 is positive, we have asymmetry.

2.2.4 Conversions between signed and unsigned

Generally when casting in C the bits are kept the same, but the interpretation changes.

There are general relationships between the same bit patterns in unsigned and two's complement. Not bothering to write them down here.

2.2.5 Signed and unsigned in C

There's some implicit casting when making comparisons in C expressions: signed is implicitly cast to unsigned.

2.2.6 Expanding the bit representation of a number

To convert an unsigned number to a larger data type, we can add leading zeroes to the representation: known as zero extension.

To convert two's complement: we add copies of the most significant bit.

2.2.8 Advice

Most languages don't have unsigned as they're more trouble than they're worth. Comparisons don't work how you'd expect, etc.

- Unsigned arithmetic is equivalent to modular addition.

C is pretty much the only language that supports them

- Actually that is not true: rust does. Seemingly because addresses are unsigned so it makes sense.

2.3 Integer Arithmetic

2.3.1 Unsigned Addition

The issue with addition is that if you have two integers, both of which can be represented by w-bit unsigned number, then their addition could require w + 1 bits. If you sum this results with another, then you've got w + 2 bits.

This is called "word size inflation", and unless restricted could mean that we take up an arbitrary amount of memory, which presumably would require lots of dynamic resizing of the words of memory used to store the number.

Lisp allows for this, but most languages put in a limit with fixed-sized arithmetic.

Unsigned addition requires discarding any bits that have overflowed the bit size determined by the data type. This is essentially results in the result being mod [max number that can be stored in the data type + 1]. So for a 4-bit number (which has a max of 15), if the sum was 21, then the result would be 21 mod 16 = 5.

Which is essentially decrementing the number by . So 4-bit = = 16. Overflow happens when the result is more than . We can detect if the result overflowed if its less than either of the operands.

2.3.2 Two's-Complement Addition

Similar to above, but taking into account negative overflow as well as positive overflow.

The way the math works out is that for:

- Negative overflow: add

- Positive overflow: subtract

- Detectable for positive overflow if x > 0 and y > 0 but s

<=0 - Detectable for negative overflow if x < 0 and y < 0 but s

>=0

2.3.4 Unsigned Multiplication

Integers x and y in the range 0 <= x, y <= 2^w - 1$ can be represented by as w-bit unsigned numbers, but their product can be between 0 and (2^w -1)^2 = 2^\{2w\} - 2^\{w + 1\} + 1.

This could require as many as 2w bits to represent. So C truncates to the lower-order w bits of the 2w-but integer product.

$(x*y) mod 2^w$.

2.3.5 Two's-Complement Multiplication

Again it truncates the same way as unsigned.

2.3.6 Multiplying by constants

Addition, subtraction, bit-level operations, and shifting all require 1 clock cycle.

Multiplication (on i7 from 2015) takes 3 clock cycles. Therefore an optimization made by compilers is to replace multiplications with constant factors with combinations of shift and addition operations.

- Examples:

- Multiplication by a power of 2:

- Shift x bits to the left, replacing with k zeroes.

- Multiplication by a power of 2:

So in order to more effectively use this a compiler might replace x*14, knowing that its the same as 14 = 2^3 + 2^2 + 2^1, with:

(x<<3) + (x<<2) + (x<<1).- Which can be simplified to

(x<<4) - (x<<1).- Although I suppose it'll still make that determination knowing how difficult it is for the given machine to do multiplication.

This all assumes that the right side of the multiplication is a known constant: either a literal or a const.

2.3.7 Dividing by powers of 2

Integer division is even slower. You can do the same as multiplication, but with a right shift instead of left shift.

2.3.8 Thoughts on integer arithmetic

"integer" arithmetic is really just modular arithmetic due to the inherent limitations of fixed word sizes.

Modular arithmetic is just where integers wrap around beyond a modulus. A 12 hour clock is modular arithmetic.

Same bit-level arithmetic operations such as addition, subtraction, etc are used on twos-complement as are used on unsigned.

2.4 Floating Point

All computers now use the standard known as IEEE floating point. Prior to this every chip maker would have their own standard.

Decimal notation for fractions:

- =

- So the digits to the left of the "decimal point" are weighted by nonnegative powers of 10, while digits to the right are weight by negative powers of 10.

For binary it's the same idea:

- Bits to the left of the "binary point" are weighted by nonnegative powers of 2, while digits to the right are weight by negative powers of 2.

So with that we can represent any fraction as a fractional decimal number in a fractional binary decimal number.

- Assuming we only have finite-length encodings, 1/3 cannot be represented exactly.

- We must therefore decide on a binary precision.

- To convert between decimal fractions to binary fractions:

- Consider the fraction as

- Then convert x into binary and move the binary point

kplaces from the right.

2.4.2 IEEE Floating-Point Representation (need to come back to this and properly understand it)

The previous section's approach is not efficient.

So IEEE:

- S: the sign that determines if the number is negative

- M: Significand is fraction number (between 0 and 1 or 1 and 2)

- E: The exponent weights the value by a (possibly negative) number.

Basically it's

- Where x determines the floating part of it and y weights it.

Bit rep is divided into three fields:

- The single bit

s - The k-bit exponent field

expencoded the exponent E - The n-bit fraction field

fracthat encodes the significand M, but the value encoded also depends on whether the exponent field equals 0.

The combined is either 32-bit (single-precision) or 64-bit (double-precision):

float:s, exp, frac= 1, k = 8, n = 23double:s, exp, frac= 1, k = 11, n = 52

There three cases of point representation:

- Normalised: When

Eis not all zeroes or ones. This is the most usual case. E is signed. M is between 0 and 1 but it's considered between 1 and 2 and the first bit is a free implied bit. - Denormalised: When

Eis all zeroes. Two purposes:- Allows us to represent numeric 0.

- Numbers very close to zero.

- Special case: When

Eis all ones. Used to represent infinity.

2.4.4 Rounding

IEEE gives 4 rounding modes. Default is to find the closest match. While the other three can be used to find upper and lower bounds.

- Round-to-even (default): i.e. round to nearest integer where the least significant digit is even. It "prefers" even. - We can do this for binary fractions too: just consider the least significant bit 0 to be even and 1 to be odd.

- Round-toward-zero: positive numbers down, negative numbers up. "towards zero".

- Round-down

- Round-up

2.4.5 Floating-point operations

Floating point ops are commutative (order doesn't matter) but not associative (parentheses do matter). This is because an operation loses precision, so the result of applying it to one parenthetical group is not the same as one of the operands with another.

This means generally compilers are very conservative when optimizing floats.

2.5 Summary

Computers encode information as bits, generally organized as sequences of bytes. Different encodings are used for representing integers, real numbers, and character strings. Different computers = different conventions of encodings.

Most machines encode signed numbers using two's complement and floating point using IEEE Standard 754.

Finite length of encodings means arithmetic in a computer is quite different to real arithmetic.

- This can cause numbers to overflow

- It can cause floats to collapse to zero when they are super close.

- This leads to oddities like

x*xresulting in a negative number due to overflow.

Unsigned and two's complement satisfy many of the characteristics of real integer arithmetic, like associativity, commutativity, and distributivity. That allows compilers to do many optimizations like the power of 2 trick.

Basically there are lots of bit-level operations that due to their relations to arithmetic operations can be exploited to get performance.

Chapter 3 Machine-Level Representation of Programs

Computers execute machine code, sequences of bytes encoding low-level operations that manipulate data, manage memory, read and write data on storage devices, and communicate over networks.

Compilers generate machine code through a series of stages.

- GCC outputs assembly, a textual representation of machine code.

- GCC then invokes an assembler and a linker to generate executable machine code.

x86-64 is a machine language (instruction set) created by Intel and still in use today. Because it's been around since 1978 it has a lot of arcane features that GCC/clang handles for us.

3.1 A Historical Perspective

- All intel are backwards compatible

- Hyperthreading introduced on the Pentium 4E, which also added 64-bit support, which was inspired by AMD.

- Core 2 - first multi-core. Dropped hyperthreading

- Core i7 - multicore and hyperthreading

- AMD developed the first 64-bit extension to Intel's IA32.

- AMD build processors compatible with the same instruction set

3.2 Program Encodings

GCC process:

- Pre-processor: expands source code to include any files specified with

#includeand any macros specified by#define. - Compiler: generates assembly

- Assembler: Generates object code - a form of machine code (binary representations of all of the instructions). But the addresses of all global values are not filled in.

- Linker: merges the object-code files along with library code to generate the final executable.

3.2.1 Machine-level code

Machine-level code format and behaviour is defined by the instruction set architecture. Most instruction sets are sequential. Hardware will optimize and run in parallel sometimes but will guarantee sequential behaviour.

Machine-level memory addresses are virtual addresses. A memory model that appears to be a very large byte array.

Assembly code is very close to machine code. It's most about that assembly is more readable.

Assembly deals with things usually hidden to the programmer of C:

Program counter: memory address of next instructionRegister file: 16 named locations storing 64-bit values. Can hold addresses (C pointers) or integer data. Used for critical state of the program, temp data like args or local vars, or returned data from a function.Condition code registers: status information about recent executed arithmetic or logical instruction. Used to implement conditional changes in control or data flow. For if and while loops.Vector registers: one or more integer or floating-point values.

C provides a model of objects with different data types allocated in memory, but machine code just views memory as a large byte-addressable array. Arrays and structures in C are just contigouos collections of bytes. Scalar types are all the same, no differnece between types of pointers, integers, etc.

Program memory includes:

- Machine code for the program

- Info required by the OS

- Run-time stack for managing procedure calls and returns

- Blocks of memory allocated by the user

The OS manages translating virtual addresses to physical addresses.

Machine instructions are very simple, e.g:

- Add two numbers in registers

- Move value between memory and register

- Conditionally branch to a new instruction address

The compiler must construct sequences of machine instructions to implement program constructs: arithmetic expressions, loops, proc calls, etc.

Assembly files contain sequences of bytes that correspond to machine instructions. Which can be sees by:

- Compiling an object-code file.

- Then using

objdumpto disassemble it. It'll show the byte offset, the bytes themselves, and the assembly code it corresponds to.

x86-64 instructions range from 1 to 15 bytes. Commonly used instructions and those with fewer operands use less bytes. The instruction format is encoded in such a way that, from a given starting position. there's a unique decoding of the bytes into an instruction. So 53 is always the starting byte (and only byte) for pushq %rbx.

Instructions like callq will need to be provided the address of the proc to call. This is performed by the linker. Prior to this an individual object file can only provide placeholder addresses for unlinked procs. They're not actually real address in the file (AFAIK). It's the linker that actually provides links to these functions to produce an executable program. Linkers also insert (or is it the compiler?) insert noop instructions to make more efficient use of space.

Lines beginning with . are directives to guide the assembler and linker.

3.3 Data Formats

Most instructions have suffixes that denote the size of the operand.

moveb(move byte)movew(move word)movel(move double word)

Different data types have different suffixes, each of which corresponds to different intel data type / c declarations.

- E.g C:

long: Suffix:q, intel:Quad Word

3.4 Accessing Information

x86 CPUs have 16 general-purpose registers storing 64-bit values. All of them are begin with %r.

Instructions can operate on different data sizes by storing them in the low-order bytes of the 16 registers. This is how can you have instructions like moveb to move a single byte even though the word size maybe be 8 bytes.

Different registers have have different conventions for how they're used. E.g %rsp is the stack pointer, used to indicate the end position in the run-time stack.

Most instructions have 1 or more operands: inputs and destinations. Source values for these can be constants, read from registers or read from memory:

- Immediate: constants are given. Start with

$. like$0x1f. Different instructions dictate different allowed values. The assembler will determine the most compact way of representing the value. - Register: The contents of a register, using 8-, 4-,2-, or 1 byte low-order portions of the register to use .

- Memory: Access some memory location according to a computed address, often called

effective address. There's a general format used to determine the address, but will have 4 components:offset: Imm,base register,index registerandscale factor. Not all are required, e.b(%rdi, %rcx). 1. The form in assembly isImm(rb, ri, s). Rb and Ri are registers,sis a scale factor. 2. The effective address is calculated byImm + R[rb] + R[ri] * s3. R[rb] just means the value of the register rb

3.4.2 Data Movement Instructions

There are many different types of movement instructions. The simplest move from one register to another and there are 4 based on data size: moveb, movw, movl, moivq.

A location can be a register or a memory address, but x86 requires one of them be a register. That's because moving from memory to memory requires going through a register.

There are conventions around how movements modify the upper bits of a destination register. There are corresponding movement instructions for each of these different space-filling behaviors.

There's an instruction that explicitly moves pre-specified registers, for space saving as its a common instruction.

%raxis used to store the returned value of a function.- Dereferencing a point in C involves copying that pointer into a register, and then using this register in a memory reference.

3.4.4 Pushing and popping stack data

Stack data operates as a last in, first out array.

As the stack grows, the top of the stack has the lowest memory address with %rsp containing the address of the top stack element.

Two operations:

pushq: pushes onto the stackpopq: pops from it

Both takes a single operand.

To push to the stack:

- Decrement the stack pointer (e.g. 8 bytes for a 64-bit address)

- Then move your address to the stack pointer register

To pop from the stack:

- Read from stack

- Increment stack pointer

3.5 Arithmetic and Logical Operations

Most of these instructions have size suffixes. There are 4 categories:

- Load effective address (leaq)

- Unary

- Binary

- Shifts

3.5.1 Load Effective Address

Variant of movq. Copies the effective address given to the memory location given. It's what & uses in C. It copies the address of a memory location into another memory location. It creates pointers.

Can also be used for compactly describing arithmetic. E.g:

- If

%rdxcontainsx, then leaq 7(%rdx,%rdx,4),%rax- will set

%raxto7 + x + (4 * x) = 5x + 7.

- Problem 3.6

- 6 + x

- x + y

- 4y + x

- 7 + x + 8x = 9x + 7

- 4y + 10

- 2y + x + 9

- Problem 3.7

- = 5x

- = 5x + 2y

- = (5x + 2y) + 8z

- = 5x + 2y + 8z

- t =

5 * x + 2 * y + 8 * z

3.5.2 Unary and Binary Operations

Unary

- Single operand as both source and dest

- Operand can either be a register or mem location

incq (%rsp)= 8-byte element on top stack gets incremented- What ++ and -- from C use

Binary ops

- Second operand is both source and dest

- So

x -= y. x is the source and destination (but it's first here, in assembly its second):subq %rax, $rdxwhere %rdx has value of x.

3.5.3 Shift Operations

Shift amount is given first and the value to shift is second. Both arithmetic and logical shifts are possible.

The shift amount can be given as either an immediate value or with the single-byte register %cl. This means that's it's possible to shift in principal by 255 (max integer encodable by 8 bits). But it depends on the value to be shifted. And so as we only have max 64-bit values, that's the top end (for w bits long, the low-order m bits are used from %cl where 2^m = w).

The different sized values again have different ops: salb (8), salw (16), sall (32), salq (64).

sal: left shiftsar: right arithmetic (fill with sign bit)shr: right logical (fill with zeroes)

Problem 3. - salq $4, %rax - sarq %cl, %rax

3.5.4 Discussion

Most arithmetic/logical ops can be used on both unsigned and two's compliment (with the exception of right shift). So (inc, dec, neg, not, add, sub, imul, order, and, sal, etc).

Problem 3.10 - t4 = !((y || x) << 3) - z

t1 = x | yt2 = t1 << 3t3 = !t2t4 = z = t3

Problem 3.11

- a: Sets

rdxto zero - b:

movq $0, %rdx

3.5.5 Special Ops

Multiplying two 64-bit integers requires 128 bit answer.

- x86 has limited ability to do this

imul/mul/divcan except two 64-bit operands and produces a 64-bit answerimul/imul/idivwith one operand will full multiply with the value stored in%rax, storing the higher-order 64 bits in%rdxand the low-order 64-bits in%rax.G

3.6 Control

3.6.1 Condition codes

In addition to integer registers, the CPU maintains a set of single-bit condition code registers. Describes attributes of most recent arithmetic or logical operation. The codes indicate what just happened and some attribute of it.

Useful condition codes:

- CF: Carry flag. Most recent op generated a carry out of the most significant bit. Used to detect over-flow for unsigned operations.

- ZF: Zero flag. Most recent op yielded zero.

- SF: Sign flag. Most recent op yielded a negative value.

- OF: Overflow flag. Most recent op caused a two's compliment overflow - either negative or positive.

leaq does not alter condition codes, as its intended to be used in address computations. Otherwise all modify.

There are instructions that only alter condition codes without modifying the registers.

CMPbehaves similar to SUB, except it sets the condition codes according to the differences of their two operands. - Set's zero flag if the two operands are equalTESTbehave similar to AND, except they modify condition codes. Commonly used to test if a register is negative.

3.6.2 Accessing condition codes

3 ways to access:

- We can set a single byte to 0 or 1 depending on some condition of the condition codes

- We can conditionally jump to some other part of the program

- We can conditionally transfer data

For setting 0 or 1, we use the SET instructions. There are several SET instructions each of which differ based on what the conditions are. The suffix refers to the conditions not the size if the operands. So setl is set less not set long.

Uses one of the low-order single-byte registers or single-byte memory location. For 32-bit or 64-bit results, the higher order bits are cleared.

The process is: we use a CMP or TEST instruction to set the condition codes, then a SET instruction to set the lower-order byte of a register (usually %eax) based on the condition code.

3.6.3 Jump Instructions

JUMP causes the execution to switch to a completely new position in the program. Generally indicated in assembly by a label defined elsewhere in the code.

During assembly, the assembler determines the addresses of all labeled instructions and encodes the jump targets as a part of the jump instructions. The target can also be read from a register - called an indirect jump, vs a direct jump in the case of a label.

There are two JUMP instructions for direct and indirect jumps, then there's a bunch that jump based on condition codes. Conditional jumps can only be direct.

3.6.4 Jump Instructions Encodings

The assembler and then the linker generate proper encodings for the jump targets - initially they're the human-readable labels in the object code.

Jump encodings are usually PC relative. They encode the difference between the address of the target instruction and the address of the instruction immediately following the jump.Offsets encoded using 1, 2 or 4 bytes.

Second encoding method: absolute address using 4 bytes to specify the target. Assembler chooses which to use.

3.6.5 Implementing Conditional Branches with Conditional Control

The general process: an if/else is broken into a labeled block for the else, and the if as an initial block with a conditional jump inserted in (as cmp or similar followed by a jump). If the condition is matched, it jumps to the else.

3.6.6 Implementing Conditional Branches with Conditional Moves

3.6.5 is the conventional way to implement control flow. But it can be very inefficient on modern processors.

An alternative is through a conditional transfer of data. It only works for simple conditions, where both outcomes of the condition can be computed, then one is chosen based on the condition.

How it works:

- So the one outcome is set to

rax. - Then another outcome is moved to another register

rdx. - Then a

cmpis used to compute the condition. - Then a

cmoveis used to conditionally moverdxtoraxif the condition was true.

This method can be more efficient due to pipelining of modern processors. Pipelined operations are broken into smaller steps, some of which can be ran in parallel. Conditional branching based on data moves allows for more efficient pipelining.

In order to keep executing efficiently (keep the pipeline full of instructions), when a CPU encounters a conditional branch (not data move), it will go down both branches as it hasn't yet computed the condition. Processes use sophisticated branch predicition logic to try to guess whether or not each jump instruction will be followed.

As long as it can guess reliably (modern processors aim for 90%), the instruction pipeline will be kept full of instrutions. Mispredicting though requires discarding work and going back down the other branch. It can be super expensive.

So conditional branches via data moves requires a fixed number of clock cycles regardless of the data being tested. So this makes it easier for the CPU to keep its pipeline full.

Not all conditions can use data moves.

- If the branch could possibly error, then branching must be used.

- Generally only the most simple expressions will use conditional moves as its hard to have enough info to reliably predict the computation required for both branches.

3.6.7 Loops

We have do-while, while, for - none of these have an equivalent instruction. So they are implemented using a combination of jumps and conditional tests.

do-while:

- Label the start of the loop

- List of the instructions of the body

- Run a condition

- Have a conditional jump that will return to the beginning of the labeled blocked if the condition passes

while:

- Two ways.

- First is called Jump to middle: 1. First an unconditional jump to a

testblock at the end of the loop 2. Another block calledloopthat contains the body of the loop 3. Run the condition 4. Conditionally jump toloopotherwise return - Second is called guarded do: 1. Translates the code to a do-while by using a conditional branch to skip over the loop if the initial test fails. 2. So the test of the while is ran first, if its false, just jump to the end. Otherwise now go into do while mode, where the body is executed then the condition, then back to the body if it passes. 3. Generally used if a higher level of optimization is required/requested (by a gcc flag).

for:

- General form:

for (init-expr; test-expr; update-expr) body-statement - Identical to:

init-expr while (test-expr) \{ body-statement; update-expr; \} - So for loops are implemented with one of the while methods above.

3.6.8 Switch Statements

Provides a multiway branching capability based on the value of an integer index. Can be efficiently implemented using a jump table: an array where the entry i is the address of a code segment implementing the action the program should take when the switch index equals i. The code performs an array reference to get the target for the jump instruction.

Benefit over lots of if statements is the time taken to perform the switch is independent of the numbers of switch cases. GCC will choose the implementation method based on the number of cases and the sparsity of case values (typically jump tables are used when the cases exceeds 3).

The compiler can do a bunch of optimizations based on the case values used (stripping the length of the integer being tested for, for example). It can take advantage of the nature of two's complement (it gets large when its negative) if the case values are all positive.

Implementation in assembly:

- Jump table defined by using the

.rodatadirective (read only data). It requires an.aligndirective to indicate the size of each address in the jump table. - Within the section, list the jump labels. Each line is the next switch case.

3.7 Procedures

Provides a way to package code that implements some functionality with a designated set of arguments and an optional return value.

Attributes that must be handled (suppose proc P calls proc Q and then Q returns P):

- Passing Control: Program counter must be set to the starting address of the code for

Qupon entry and then set to the instruction inPfollowing the call toQupon return. - Passing Data:

Pmust be able to provide one or more parameters toQandQmust be able to return a value back toP. - Allocating and deallocating memory:

Qmay need to allocate space for local variables when it begins and then free that storage before it returns.

x86 implementation of procedures involves a combination of special instructions and a set of conventions on how to use machine resources. It makes a big effort to minimize the overhead in calling procedures.

Key feature: Most languages make use of last-in, first-out memory management (a stack).

- While

Qis running, only it needs the ability to allocate new storage and to set up calls to another procedure. The calls prior toQare suspended. - When

Qreturns, storage it used needs to be freed. - Therefore a stack can be used to manage the procedures in a program.

x86 provides a stack for implementing the call stack. %rsp points to the top element of the stack. Data can be stored and retrieved with pushq and popq. Space can be allocated be decrementing the pointer; space can be deallocated by incrementing the pointer. The region of space is called its stack frame.

The frame for the current procedure is always at the top of the stack.

When calling another procedure, the return address will be pushed to the stack before the new procedure's frame is added. The return address is stored in the caller's frame. Most of the time the stack frames are the same size.

x86 supports 6 integral values in a frame; if a procedure requires more, the previous stack is used.

Not all procedures require stack frames: if they don't call anything and have arguments that fit within the registers, no frame is needed.

3.7.2 Control Transfer

Passing control only requires setting the program counter to the starting address of the procedure's code. The instruction to call a procedure will first push the return address onto the stack and the set the PC.

call: operation to call a procedure: handles pushing the return address and setting the PC. The target is the address of the procedure and can be either indirect or direct (whether a label is used or a memory address).

ret: operation to return from a procedure: pops the return address and set the PC to it

3.7.3 Data Transfer

Most passing of data as arguments is done via registers. For example, arguments are passed into %rdi, %rsi, and values returned via %rax. The available registers are %rdi, %rsi, %rdx, %rcx, %r8, %r9 for 64 bit registers (there are others for 32, 16, and 8 bits). They must be used in that order.

When a function has more than 6 arguments, the others are passed on the stack. They are stored in the stack frame of the calling procedure. Arguments on the stack are rounded up to multiples of 8. %rsp is the pointer for the top of the stack, so it's used when adding arguments from the stack.

3.7.4 Local Storage on the Stack

Sometimes procedures need more storage that what's available via registers:

- More local data than registers

- The address operator

&is used so we need to generate an address for it - Some local vars are arrays or structures.

Typically procedures allocate space on the stack frame by decrementing the stack pointer. It will do this at the beginning of the procedure. Afterwards space in the stack is referred to in relation to the decremented stack pointer and an offset in multiples of 8 bits.

3.7.5 Local Storage in Registers

As program registers are shared among all procedures, there are conventions that prohibit overwriting registers used by callees.

callee-saved registers must be preserved by the called function, so that when it returns, their values are the same.

caller-saved registers can be used by the callee however it wants.

3.7.6 Recursive Procedures

Creating stacks for each procedure call naturally allows for recursive procedures.

3.8 Array Allocation and Access

Allocating space for an array requires the size of the data type and an integer representing multiples of that size. An address pointing to the beginning of the allocated space is then given.

This can easily translate to machine code (as the mov instruction is specified in a way easily compatible with array indexing notation).

3.8.2 Pointer Arithmetic

C allows for easily modifying pointers using simple arithmetic. An integer i can be added to an address to get the address to get the ith element in an array.

3.8.3 Nested Arrays

Nested arrays are stored in row-major order, meaning contiguous layout. The compiler generates the appropriate offsets to index into a multi-dimensional array.

3.8.4 Fixed-Sized Arrays

A bunch of optimizations can be made if arrays are fixed size. I'm not going to go into what they are - way too much information.

3.8.5 Variable-Sized Arrays

Historically C didn't allow for variable sized arrays. But C99 introduced it. It's essentially the same as fixed-size, but the computed size of the array is loaded into a register and that's used as in calculating the offsets required when reading into the array.

As this requires a multiplication instruction (instead of a combination of shifts and adds that are used for fixed-size), it can have a decent performance hit.

When a variable-sized array is used in a for loop, the compiler can exploit the regular access patterns to make the address computation more efficient.

3.9 Heterogeneous Data Structures

In C, two types for combined types: structures and unions.

3.9.1 Structures

A data type that groups objects of possibly different types into a single object, with each object given a label.

Similar to arrays, data is laid out contiguously, with the compiler storing the size of each label and using that for computing address lookup.

3.9.2 Unions

Allows a single object to be referenced according to multiple types. Declared with a similar syntax to structs. But instead of storing each named field, it stores only one of them, with the size of the union being the max size of all of the fields.

They're dangerous as we're circumventing the type system. But they're space-saving if we know that any of the fields are mutually exclusive.

Example: to create a binary tree, we need a node. But a leaf node will have a value, whereas internal nodes have children and no value. Using a struct would always waste data whereas a union will use only what's needed.

3.9.3 Data Alignment

Typically computer systems restrict allowable addresses of primitive types, requiring the address to some multiple of K (typically 2, 4, 8). This simplifies hardware design between the processor and the memory system. So a double of 8 bytes can always be retrieved with one memory operation. Being able guarantee simplistic lookups improve memory performance.

Often, with data types like structs, the natural layout of data could result in addresses that are not aligned in a given multiple. So often the compiler will pad different fields in a struct to ensure data alignment.

3.10 Combining Control and Data in Machine-Level Programs

3.10.1 Understanding Pointers

- Every pointer has a type (malloc returns a generic pointer

void) - Every pointer has a value (except NULL(0) which indicates it points nowhere).

- Pointers are created with &

- Pointers are dereferenced with *

- Arrays and pointers are closely related - array referencing is essentially the same as pointer arithmetic a dereference

(*(a+3)), with both being scaled by the object size. - Casting pointers changes its type but not its value

- Pointers can also point to functions

3.10.3 Out-of-Bounds Memory References and Buffer Overflow

C does not perform any bounds checking on array references. And with local variables stored on the stack along with state information like register values and return address, unchecked memory access could read or write to parts of the program outside of the function.

This is a buffer overflow. A typical case is allocated space for a string, but then a value larger is written to it, overflowing into the rest of the stack frame and beyond. Carefully crafting the bytes could lead to arbitrary code execution

“3.10.4 Thwarting Buffer Overflow Attacks”

Buffer overflows require injecting code into a known address so that it can be provided as a return address. Historically stack address were highly predictable across machines (known a a security monoculture).

Stack Randomization Stack randomization randomizes stack addresses by adding some random number of bytes to the start of a program. Needs to be large enough to cause sufficient randomization but small enough to not consume too much memory. Typical randomization can be around 2^32.

Apart of a class of techniques called address-space layout randomization, or ASLR. Essentially randomization around how all data for a program is stored in memory.

But it's still possible to circumvent this. An attacker can add a bunch of no-ops to force the PC to go through a large address space. As long as the exploit code is in there somewhere, it'll eventually hit. It's called the "nop sled".

Stack Corruption Detection A way to detect buffer overruns. GCC can incorporate a stack protector. Idea is to store a canary value (also called guard value) in the stack frame between any local buffer and the rest of the stack state. Its value is random so there's no easy way to determine what it is.

Before the register state and returning from the function, the program checks if the canary has been altered and if it has it aborts with an error.

GCC will try to detect if a function is vulnerable to an overrun and insert the protection automatically. Based on whether there's a type char in the function.

Limiting Executable Code Regions Memory is broken into pages, with a given page containing a single bit that determines it's access (read, write, executable). A program contains both read/write and executable regions. For safety we should only execute code we actually intend to execute and allow the others be only read and/or write.

Historically Intel required read/write to also be executable. But now (prompted by AMD), it's possible to have read/write but not executable. So now the stack can be read/write and not executable.

Checking whether a page is executable is done in hardware so has no penalty in efficiencies.

JIT compilers require dynamically executing code (like JVM) so it can't be offered the same protection.

3.10.5 Supporting Variable-Size Stack Frames

Sometimes functions require space dynamically, such that the compiler cannot ahead of time determine the space required. E.g. using alloc or declaring a local array of variable size.

To handle this, x86 uses %rbp to serve as a frame pointer (or base pointer, hence bp in %rbp). As it's a callee-saved register, it must be reverted after the function returns.

%rbp is set to the stack pointer %rsp at the beginning of the procedure and remains there for the duration. Remember that the stack pointer is always pointing to the top of the stack so the only way it can be used to access local variables is by pointer addition of known sized local variables, as allocating dynamically would change the required offset to an unknown amount. It would essentially need to know how big the dynamically allocated space is so it could "jump" over that region to the local vars.

But with rbp, it will always be pointing the the base of the stack, so local variables can now referred to relative to the base pointer (as they have known sizes so their locations can be inferred). They are allocated at the beginning of the stack frame after the base pointer is saved. Then after local vars, any dynamic space is allocated (with the stack pointer still pointer to the top of the stack which is not determinable at compile time).

At the end of the function the stack pointer is set back to the base pointer (rather than use arithmetic as again the size of the stack is not known). This effectively deallocates the frame.

Frame/base pointers are only used when variable allocation is needed. So it's considered an optimization.

3.11 Floating-Point Code

Since Pentium/MMX in 1997, Intel and AMD have used media extensions to support graphic and image processing. These originally focused on allowing single instruction, multiple data SIMD (sim-dee). In this model, the same operation is performed on multiple data in parallel. There have been multiple versions of the media extensions. MMX -> SSE (streaming SIMD extensions) -> AVX (advanced vector extensions).

With each extension there have been new registers, supporting 64, 128, and 256 bit values.

Starting with SSE2 in 2000, the media instructions have support floating point data, using single values in the low-order 32 or 64 bits of XMM or YMM registers (which go along with AVX). To use them, it needs to be in scalar mode.

3.11.1 Floating-Point Movement and Conversion Operations

There are dedicated instructions for copying floating point data into the XMM/YMM registers and memory. There are also instructions for converting to integer values. When converting from floating-point to integer, they are truncated, rounding values towards zero.

There's also a dedicated floating point register %xmm0 for returning floating point data from procedures.

3.11.2 Floating-Point Code in Procedures

XMM registers are used for passing floating point data to procedures. There are 8, with more being passed via the stack. They're all caller save - the callee can overwrite without saving.

3.11.3 Floating-Point Arithmetic Operations

There are instructions for all arithmetic operations for both single (32) and double (64) precision floats.

3.11.4 Defining and Using Floating-Point Constants

Unlike integer arithmetic operations, AVX floating-point instructions can't have immediate values as operands (as there's no way to accurately represent them). So the compiler must allocate and initialize storage for any constant values.

3.11.5 Using Bitwise Operations in Floating-Point Code

There are dedicated instructions for bitwise operations on floating-point data.

3.11.6 Floating-Point Comparison Operations

There are two instructions for comparing floating point values, one for single, one for double. Similar to CMP instruction, in that they compare values and set the condition codes.

An extra condition flag is used called parity flag which is used to indicated NaN (in integer it's used to indicate whether the result was even).

3.12 Summary

In this chapter, we have peered beneath the layer of abstraction provided by the C language to get a view of machine-level programming. By having the compiler generate an assembly-code representation of the machine-level program, we gain insights into both the compiler and its optimization capabilities, along with the machine, its data types, and its instruction set. In Chapter 5, we will see that knowing the characteristics of a compiler can help when trying to write programs that have efficient mappings onto the machine. We have also gotten amore complete picture of how the program stores data in different memory regions. In Chapter 12, we will see many examples where application programmers need to know whether a program variable is on the run-time stack, in some dynamically allocated data structure, or part of the global program data. Understanding how programs map onto machines makes it easier to understand the differences between these kinds of storage.

Machine-level programs, and their representation by assembly code, differ in many ways from C programs. There is minimal distinction between different data types. The program is expressed as a sequence of instructions, each of which performs a single operation. Parts of the program state, such as registers and the run-time stack, are directly visible to the programmer. Only low-level operations are provided to support data manipulation and program control. The compiler must use multiple instructions to generate and operate on different data structures and to implement control constructs such as conditionals, loops, and procedures. We have covered many different aspects of C and how it gets compiled. We have seen that the lack of bounds checking in C makes many programs prone to buffer overflows. This has made many systems vulnerable to attacks by malicious intruders, although recent safeguards provided by the run-time system and the compiler help make programs more secure.

“We have only examined the mapping of C onto x86-64, but much of what we have covered is handled in a similar way for other combinations of language and machine. For example, compiling C++ is very similar to compiling C. In fact, early implementations of C++ first performed a source-to-source conversion from C++ to C and generated object code by running a C compiler on the result. C++ objects are represented by structures, similar to a C struct. Methods are represented by pointers to the code implementing the methods. By contrast, Java is implemented in an entirely different fashion. The object code of Java is a special binary representation known as Java byte code. This code can be viewed as a machine-level program for a virtual machine. As its name suggests, this machine is not implemented directly in hardware. Instead, software interpreters process the byte code, simulating the behavior of the virtual machine. Alternatively, an approach known as just-in-time compilation dynamically translates byte code sequences into machine instructions. This approach provides faster execution when code is executed multiple times, such as in loops. The advantage of using byte code as the low-level representation of a program is that the same code can be "executed" on many different machines, whereas the machine code we have considered runs only on x86-64 machines.

Chapter 4 - Processor Architecture

This chapter describes the architecture of a processor by creating a fake instruction set called Y86-64, a simplified version of x86-64.

I won't make extensive notes on the ISA specifically, but will make notes on the new information it introduces.

4.1.3 - Instruction Encoding

Each instruction, along with any data required for that instruction, needs to be encoded. This is determined by the ISA.

How the bytes in an instruction are used:

- Instructions can reuse code from other instructions, if there share functionality. This is determined by the lower-order 4 bits in the initial byte of the instruction.

- Another byte can be used to specify registers that should be used as operands.

- Another byte that is used for some instructions is a constant word, used for immediate data.

All instructions must have a unique interpretation.

There are two main types of instructions sets, CISC and RISC:

- CISC are complex instructions sets like x86-64 and represent a gradual increase in complexity as new features were added to ISAs. Instructions can be in the thousands.

- RISC is the opposite worldview, where the instruction set is specifically restricted, allowing for much simpler and efficient hardware. Instructions are typically less than 100 (nowadays RISC is more complex with more instructions but still small relative to CISC).

Generally this means that compilers targeting RISC have to do a lot more work than CISC as complex behaviors have to be constructed from simpler instructions rather than using an existing one provided by the ISA. For example, RISC ISAs have no condition codes, instead requiring the result of a condition be stored in an explicitly provided register. They also have simple addressing, just base and displacement.

4.1.4 Exceptions

A program's state can be accessed via a status code, with an enum of states based on what's happening. E.g. invalid memory access, invalid instruction, etc.

4.2 Logic Design and the Hardware Control Language HCL

0s and 1s are represented by either the presence of a high or low voltage, with high = 1v and low = 0v.

Three major components are required for a digital system:

- Combinational logic: compute functions on bits

- Memory elements: to store bits

- Clock signals: regulate updating of memory elements

Modern processors / digital circuits are designed by using an HCL, from which a real schematic can be derived.

4.2.1 Logic Gates

Logic gates are the basic computing elements for digital circuits. They generate an output equal to some Boolean function on the bit values of their inputs. The are always active (always producing an output).

4.2.2 Combinational Circuits

Combinational circuits are a network of logic gates.

Rules for circuits:

- All gate inputs must be connected to either: 1) a system input (primary input), 2) the output of a memory element, 3) the output of a logic gate.

- Outputs of two or more logic gates cannot be connected together.

- The network must be acyclic.

Multiplexor: switches between two inputs based on a control input.

4.2.3 Word-level Combinational Circuits

Circuits are designed to operate on data words, but they're constructed from logic gates that operate on the individual bits of the input words. The HCL allows the specification of the word size and the circuit will be constructed accordingly.

Multiplexors are designed using switch-like expressions in the HCL. They can be built from more than just two inputs. The control input can also be a two-bit binary number, allowing for more conditions based on the control.

An example of this is the ALU (arithmetic/logic unit). It supports the 4 integer operations from x86: addition, subtraction, AND, OR. Based on two inputs, the control input switches between these 4 operations. Note in modern processes the ALU is responsible for instruction execution and supports many more operations than the 4 listed here.

4.2.4 Set Membership

It's common in circuit design to want to compare a signal to a number of possible matching signals. We can model this in HCL using set notation.

4.2.5 Memory and Clocking

Combinational circuits, by their nature, do not store state, and instead simply react to input signals, generating output signals based on some function.

To create sequential circuits we need devices that store information represented as bits.

Storage devices are controlled by a single clock, a periodic signal that determines when new values are loaded into devices.

There are two types of memory devices used in circuits:

- Clocked registers: store individual bits or words. The clock signal controls when to change state based on the clocked register's input.

- Random access memories: stores multiple words addressable by an address.

In hardware a register means a storage device directly connected to the circuit by its input and output wires. In machine-level programming, registers represent a small collection of addressable words in the CPU.

A hardware register stores its input as internal state, but only updates when the clock signal is "high", even if the input is different. Registers serve as barriers between the logic in a circuit - they stop the signal from flowing through the circuit unimpeded.

Registers are written to and read from via the register file, an array of registers containing multiple ports that allow the simultaneous updating multiple registers. The ports define which port and what to update it with and the update happens with the rising of the clock signal.

4.3 Implementation of a CPU from an ISA (renamed from the real chapter name for my own understanding)

4.3.1 Organizing Processing into Stages

In general, processing an instruction involves a number of operations. We organize these into a sequence of stages, with each instruction following a uniform sequence of stages. Having uniform stages allows the best use of the hardware.

Operations:

- Fetch: Reads bytes of an instruction from memory, using the program counter as the memory address. From the instruction, two 4-bit portions are extracted, the first called the icode (the instruction code) and the second the ifun (the instruction function). It can also fetch a register specific byte or an 8-byte constant word. It then computes the next instruction which is simply the PC plus the length of the fetched instruction.

- Decode: Reads up to two operands of the instruction from the register file.

- Execute: The ALU performs the operation specified by the instruction (according to ifun), computes the effective address of a memory reference, or increments or decrements the stack pointer. Condition codes are also possibly set.

- Memory: May write data to memory or read data from memory.

- Write back: Writes up to two results to the register file.

- PC update: Set to the address of the next instruction.

A processor loops indefinitely, performing these stages.

Note: 5 stages were typical of a 1980s processor. Nowadays they can have > 15.

It's up to the processor to map the instructions it provides in its ISA to these stages.

4.3.2 Hardware Structure

A sequential CPU would treat each stage a sequential operation, with each stage happening in order. The building of a sequential CPU requires a combination of hardware registers with values passed via single bit wires, hardware units (ALU, memory, etc) that perform some dedicated function, and control logic that switch between input signals.

4.3.3 SEQ Timing

Many elements of a CPU (the combinational logic, reading from random access memory) are all stateless operations based on some input. So timing/sequencing is therefore only dependent on a few stateful hardware units:

- Program counter

- Condition code register

- Data memory

- Register file

These are controlled via the clock signal that controls loading new values into registers and writing values to random access memories.

- PC updated on every clock cycle

- Condition code register only updated when an integer operation is executed

- Data memory is written only when

rnmovq, pushq, callare executed. - The two write ports of the register file allow them to be updated each clock cycle but the special register ID

0xfindicates that no write should be performed.

Clocking these 4 units is the only thing required to control sequencing.

All other units can be executed simultaneously (which naturally happens because updating the signal updates all dependent circuits simultaneously) because they adhere to the principle of no reading back: the processor never needs to read back the state updated by an instruction in order to complete the processing of this instruction. This allows a instruction to essentially act as if each stage where executed sequentially, even though in reality it all happens at the same time. It's basically just a pure function of an input.

So essentially all CPU operations are either combinational logic or controlled by the clock signal.

The problem with sequential CPUs is that the clock cycle has to be slow enough to allow signals to propagate through the circuits before starting the next clock cycle. That's where pipelining comes in.

4.4 General Principles of Pipelining

Pipelined CPUs act like a car wash: multiple cars can be in the process of being washed, with each in a different stage. Each car moves through each stage before finishing. A car must pass through each stage, even if it doens't require it, like waxing.

A key feature of pipelining is that increases throughput in the system but it may increase latency (as it would be quicker to skip steps it doesn't require).

4.4.1 Computational Pipelines

Each stage of the car wash is a stage in the instruction execution and the cars are individual instructions.

Pipelining a CPU requires the saving and loading of register states for each stage in the pipeline per clock cycle. So after each clock cycle, for each stage an instruction's progress through the stage is saved. Then the next clock cycle its's loaded into the next stage.